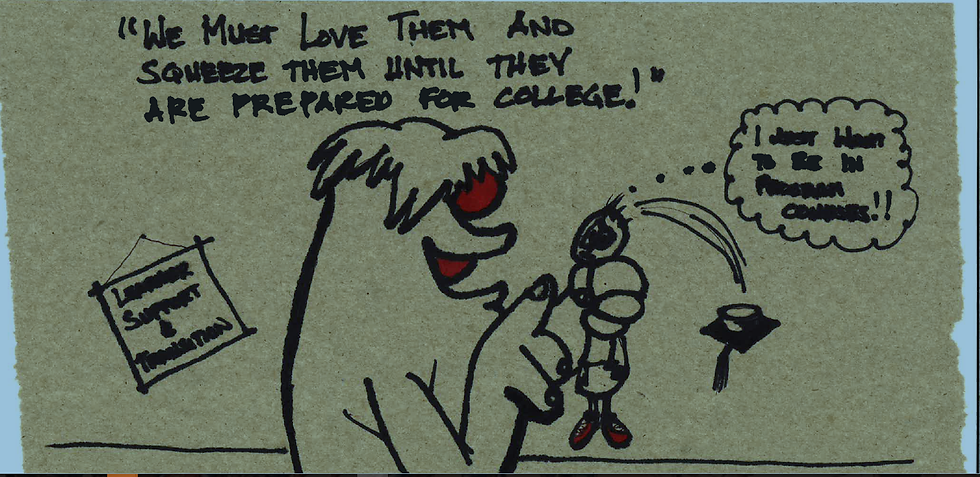

The power of language has always been a true love of mine. It is probably a bit of rationalization on my part since I'm not a very visual person, but I've always loved when I (or someone else) says something that simply and succinctly makes a point in a way that anyone could grasp. It's even better if the point is so good, no one can disagree, but that can be too much to ask. Strengths and weaknesses always seem to be two sides of the same coin and my verbal strengths have always been balanced by an inability to represent my ideas in pictures, charts, sculpture, painting, or any other visual medium. As I've gotten older, I've become more comfortable with my weaknesses and find myself drawn to people with the gift of capturing ideas visually. One of those people is my friend Mike (pictured). Mike has a gift for capturing my sometimes random ideas visually, often on a piece of paper towel:) A couple of years ago, I was trying to capture our switch from an old model of developmental education, where we "fixed" people and basically never let them go, to a "just-in-time" model that helps people where they actually are and need to be.

I was drawing stick people on a board and Mike just watched. Later that afternoon, he handed me a paper towel with this character drawn on it. Our old model was the Abominable Snowman and our students were Daffy Duck just yearning to be free. One picture said it all brilliantly. I've included the picture above, but this video also gives you the idea.

A few days ago I was trying to tell Mike about a shift I think a poverty-informed college must make. I was working on some tortured analogy about Harry Potter and the Sorting Hat (I called it tortured here too), but it wasn't capturing the idea I hoped for. I wanted to show we weren't here to eliminate the unworthy, but rather to create opportunity for the widest group possible. This hit a chord with Mike and he described a conversation he had been in where someone had said, "we are a filter, not a pump" in an attempt to justify "weeding out" as a college practice. Mike and I agreed if filtering had ever been a good idea, it certainly wasn't now, and I left to go back to my day. The analogy stuck with me and the next day, I thought I would be funny and tell him I had extended the analogy to me being a plumber breaking up clogs. I even joked I was going to come to meetings with a plunger from

now on to unclog the system for students. Later that day, this picture showed up in my email. On one paper towel, Mike had captured exactly what poverty-informed practice should be doing. My admiration for visual people grows.

This filter versus a pump mentality is worth calling out. As we move toward the most inclusive poverty-informed environment possible, we need to identify our filters and see if we can remove them. One of the toughest changes my college has made in the last two years was a de-emphasis on placement testing. As I've noted before, if you try to change an entrenched system, the resistance will be huge, and this was true with our assessment and placement work. It was common knowledge we weren't doing placement very effectively, and that was mirrored across the nation at colleges like ours. However, there was a deep level of attachment to the testing system we had. The reaction to the changes seemed almost personal, and that always confused me because the people involved were generally reasonable and would consider themselves advocates for students. I think the real subtext of the discussion was the change from a filter mentality to a pump mentality. We had used placement tests to filter students or protect them from themselves. The latter seems almost noble until you really start to unbundle it. One of our premises in our poverty-informed work is what students know on day one is not a very good indication of what they can learn. So, instead of filtering them out at the beginning (which was reality because the transition from remedial coursework wasn't very good), we were shifting to a mindset of building structures that helped our students successfully move through... you know, like a pump. Protecting students from themselves seems paternalistic to me. Eliminating unnecessary barriers and walking beside them seems like a partnership.

The pump is a great analogy because it isn't one size fits all. One of the persistent questions I get about the students I advocate for is, "shouldn't we treat them the way we treat the rest of the students?" This is a loaded question because the assumptions behind it are everything. If people meant we try to give all students what they need, then this makes perfect sense. Unfortunately, most times the question seems to imply we should just give everyone the same thing. This thinking is flawed on two levels. First, there is a difference between equitable and equal, a huge difference. Most people understand this. I think the more insidious flaw in asking people with significant barriers to access the system other students do, in the same way, is the system was not designed for them. Does that make sense? Because I think it's a big deal. College systems are built on assumptions of who they will serve. It seems natural those assumptions would not be about students with the greatest barriers. So, until the day we start building our systems that way, let's build effective pumps to help them navigate plumbing that wasn't always designed with them in mind. This is different than building separate systems. It is adding appropriate support at points in the system where students have historically struggled. Essentially we are installing a pump with the appropriate pressure to move them past a potential clog. These are poverty-informed supports, and if we built our systems with students from poverty first in mind, they might not be necessary, but I don't think that is likely or practical. So, we build in supports to navigate an inherently flawed system and use what we learn to improve it. That is poverty-informed in my opinion.

Filters, pumps, and plumbers seem like a great way to represent a technical college learning to serve its students in new and more effective ways. Perhaps there was a time where deciding who should be in college and who shouldn't was ok, although I doubt it since it was instructive to see who was excluded. But even if that time existed, it has passed. My father told me when his high school class graduated in the late 1960's, a number of his classmates moved to southern Wisconsin and took jobs at an automotive plant. Those were the kind of jobs a high school graduate could build a life on, a life that provided for a family. That layer of employment has essentially left our economy, and we have told young people post-secondary credentials are the key to success in the new economy. I believe that to be true, so I also believe filtering students out is a process of picking economic winners and losers, and we do not belong in that business. In a "post-secondary education for all" world, it is incumbent on colleges to adapt to the new world as well. We need to get out our wrenches, and yes our plungers, unclog the filters, and install pumps wherever we need to. It took me five paragraphs and Mike got it in one drawing...

Comments